| THE MYTHS OF SUEZ |

|

|

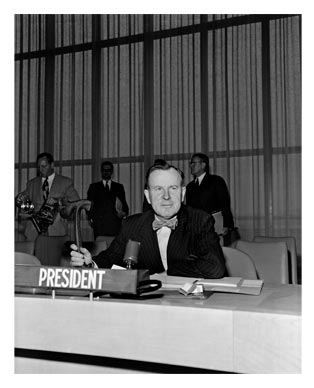

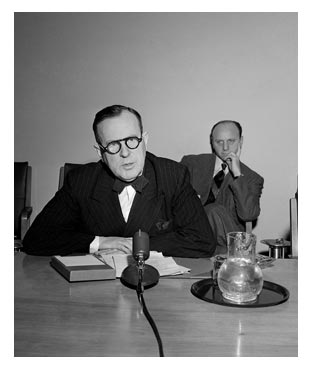

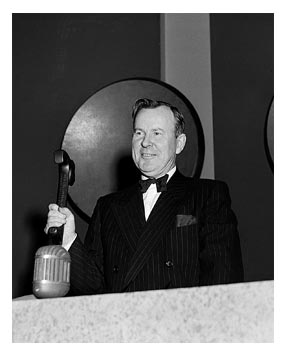

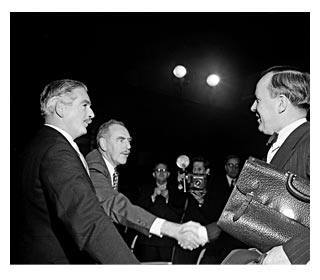

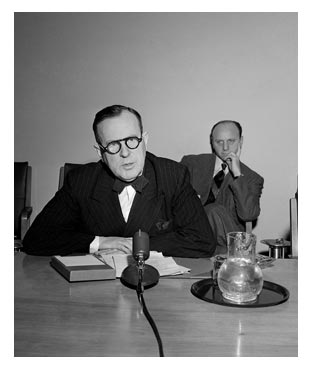

December 11, 1957. Inside a massive auditorium at the University of Oslo, they have gathered to hear the son of a Methodist minister born in an obscure village in Southern

Ontario. Up until June of this year, he was Canada’s foreign minister but then in the general election, he and his colleagues were thrown out of office. Now Lester Pearson is a backbench MP in Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition. He is 60 years old and possibly the most famous Canadian in the world. When he speaks, his words echo all over his home and native land.

“A great gulf... has been opened between man's material advance and his social and moral progress, a gulf in which he may one day be lost if it is not closed or narrowed. Man has conquered outer space. He has not conquered himself.”

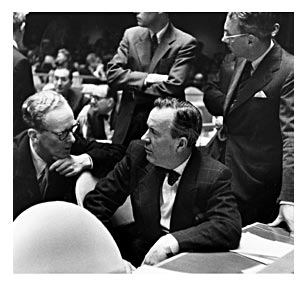

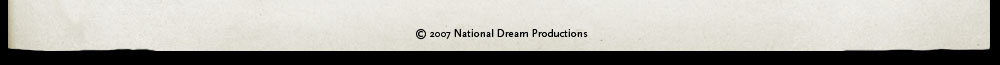

Pearson is here because 13 months before this ceremony, during the convulsive Suez Crisis, Canada’s greatest diplomat was carving out a jagged path back to peace and sanity. In that dark winter of 1956, while the western alliance was falling apart, while the Commonwealth shuddered to near breaking point, while 3 invading armies tore through Egypt, Pearson moved, the calm eye of the storm, through the UN General Assembly persuading delegates to create the first ever UN peacekeeping force. This international force landed in Egypt within weeks of Pearson’s proposal allowing the 3 foreign armies – British, French, Israeli – to withdraw.

Arguably Pearson was the only diplomat who could have bridged the divisions between allies and enemies, who had the necessary contacts and trust in the centres of power, who had the essential sense of tactics to achieve in just a matter of days what had been talked about for years.

Celebrated around the world, the peacemaker was condemned by many at home for having betrayed Canada’s two Mother Countries in their hour of need. But inexorably, his Peace Prize triumph will smooth over the bitterness and criticism. In a land of few myths, Pearson’s aura of peace will fundamentally define the way Canadians want to see themselves in the world.50 years later, so many myths have now enshrouded Pearson’s stunning diplomacy, that it is difficult to remember accurately why and how he managed his diplomatic masterpiece. On the 50th anniversary of his Nobel Prize award, it is time to look past the fog.

|

|

MYTH 1:

Lester Pearson Single-Handedly Invented Peacekeeping

Not in his memoirs, not in any public statements did Pearson ever claim to invent peacekeeping. His ingrained humility would not allow for any bragging or false claims. His innovation and genius lay in the execution, the strategising, the coordination – the actual live play of diplomacy under high intensity conditions. When he gave his full account of the crisis to the House of Commons on November 27, 1956, Pearson said: “There was nothing new in either the idea or in its proposal and no one on this side of the House, I am sure, wants to take credit for having put forward a novel and valuable proposal. I hope it was valuable but it certainly wasn’t novel; except in the sense that it was adopted – but in no other respect.”

Diplomacy does not unfold in a vacuum and Pearson certainly had precedents to build on. In the late 1940s, the UN sent unarmed observers to Palestine and Kashmir. In 1950, it had sent an army to Korea. Pearson’s “peace and police force” fell neatly in between the two poles. Over the years, various calls had been made for some kind of UN force to be stationed along the Egyptian Israeli border. Pearson had raised the idea himself in November 1955 with British PM Anthony Eden who turned it down.

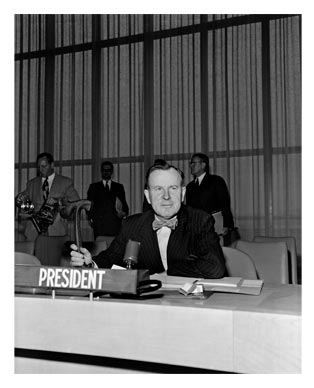

While Pearson was absolutely critical in the getting the General Assembly to vote for UNEF (United Nations Emergency Force), the actual force was a collective triumph – with major credit going to UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold, one of his key advisors, Ralph Bunche and UNEF’s first commander, Canadian General Tommy Burns.

|

|

MYTH 2:

Lester Pearson Stopped the Invading Armies During the Suez Crisis

On November 4th 1956, against incredible odds, Pearson won approval for his peacekeeping proposal in the UN General Assembly but he didn’t actually make the peace in Egypt. This was beyond the scope of any middle power. Only a super power could enforce peace against the will of two European heavyweights. So it was the United States – utterly exasperated with Great Britain and France’s military action – which actually made the peace. Using a brutal form of soft power, Washington threatened to gut the British currency and essentially blackmailed the UK into withdrawing their armies. Pearson had no illusions about how the peace in Suez was actually made. But his genius was to think ahead to the need - once peace had been forced down throats – for a respectable exit route. His peacekeeping proposal provided the exit.

|

|

MYTH 3:

Lester Pearson Thought Peacekeeping was a Long Term Solution

The pragmatist had served on the world stage too long to believe in any permanent solutions to the endless flow of international emergencies. He thought UNEF was a temporary fix and acknowledged the limitations during his Nobel lecture.

“I do not exaggerate the significance of what has been done. There is no peace in the area. There is no unanimity at the United Nations about the functions and future of this force. It would be futile in a quarrel between, or in opposition to, big powers. But it may have prevented a brush fire becoming an all-consuming blaze at the Suez last year, and it could do so again in similar circumstances in the future. We made at least a beginning then. If, on that foundation, we do not build something more permanent and stronger, we will once again have ignored realities, rejected opportunities, and betrayed our trust.”

During the crisis, a peacekeeping force was only one part of Pearson’s initial proposal. He had also argued for a major conference to create a long term solution to the Arab Israeli conflict. From the General Assembly podium, he warned: “Until we have succeeded in this test of a political settlement, our work today...though [it] may give us some reason for hope and encouragement, remains uncompleted.”

As he spoke those words, he must have suspected the moment for any settlement would be very short lived. He told the CBC years later: “You can do things under the incentive of terror and fear that you can't do once the fear disappears. And there was a time, one week, ten days when the Assembly could have passed a resolution, I think, that could have provided the basis for a political settlement, which would have been imposed by the United Nations. That moment soon passed once the danger of world war passed.”

|

|

MYTH 4:

Lester Pearson was a Neutral Bystander

Modern day Canadians enamoured if not befuddled by our image as kindly hearted peacekeepers might be surprised to realise that Pearson was not some kind of disinterested observer watching calmly from the sidelines.

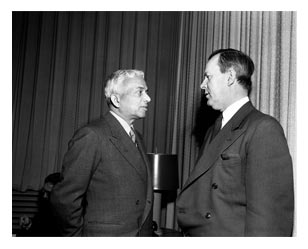

The Suez Crisis erupted at the height of the Cold War and tore apart the Western alliance. Britain and France had ignored Washington’s repeated pleading not to take any military action against Egypt. Pearson was appalled if not horrified by the growing rift between Canada’s two closest allies. “I could see trouble developing. I wasn't thinking of trouble in terms of a war in Palestine. I was thinking of trouble in terms of a grave difference of opinion between London and Washington. That always gives a Canadian nightmares, of course. “

All through the exchange of diplomatic cables, one can read Pearson’s deep anxiety about the divergence. It is no exaggeration to say that he proposed peacekeeping to save the British from themselves and to heal the fury poisoning the Western alliance. In fact, such was his determination to save the UK from condemnation that in the early hours of the crisis, he first proposed simply declaring the invading British forces to be UN forces. He only moved away from this desperate stab when Washington flatly rejected it saying quite rightly that this would absolve and legitimise the British invasion.

|

|

MYTH 5:

Lester Pearson Played a Competely Independent Role in the Crisis

It is commonplace to hear the call for an “independent” Canadian foreign policy. Pearson paid some lip service to this idea but perhaps the more definitive word in his world view was “interdependence”.

Given that Canada has never been in a position to order around allies or intimidate enemies, her diplomacy must follow the art of the possible. Pearson was always keenly aware of the limitations of Canada’s influence. He had learned over many decades not to over reach.

To make UNEF a reality, he did not – indeed could not - act with complete independence. Pearson succeeded in large part because throughout the crisis the Middle Power diplomat had the full backing of the United States. Indeed, he could not have achieved anything without their support. He took this as a given. He also needed London to if not accept his proposal, then at least not to torpedo it.

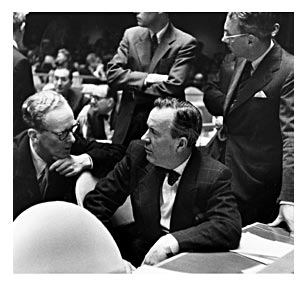

In his Nov. 27 address to the House of Commons, he openly acknowledged this collaboration: “We were anxious to keep in close contact with our friends in Washington and our friends in London...because while a good many of these things are desirable in principle, there is not much point in putting them forward at the United Nations if they are going to be opposed at once by all of our friends. Therefore we were anxious to get the views of both London and Washington.”

And if anyone wants a lesson in the limitations of middle power diplomacy, one just has to read the cables between Pearson and his brilliant High Commissioner in London Norman Robertson. Following instructions from Pearson, Robertson spent countless hours trying to restrain the British from using force to settle the dispute. He was always courteously received but his fine words had absolutely no effect – and this at the supposed height of our middle power influence. He ultimately exasperated British Prime Minister Eden who wrote on one record of a discussion with Robertson that he saw no need to ask Robertson’s opinion anymore.

|

|

MYTH 6:

Lester Pearson was a Pacifist

This myth seems to flow backwards from Suez to wash over Pearson’s entire career. Canadians admire him for the Peace Prize but are probably blissfully unaware about his central role in proposing and shaping the most powerful military alliance in history, NATO. They also might forget that as a young man he signed up to fight in the Great War and even considered quitting his post during the Second World War to sign up again. He supported dropping the atomic bomb on Japan to end the fighting. He approved Canada’s massive military spending during the Cold War. He willingly sent Canadian troops as part of the UN force into Korea to push back the North Korean army. He also agreed to accept nuclear weapons when he became Prime Minister.

He was a man of peace but he had few illusions about how to confront the Soviet threat. In a campaign speech in 1962, he said: “We must of course remain strong in our defence forces in the free world to prevent aggression until we can find a better foundation for peace.”

|

|

MYTH 7:

All Canadians Supported Pearson's Diplomacy During Suez

5 decades after Pearson won his Nobel Peace Prize, most Canadians probably see peacekeeping as a defining national trait. But in 1956, Canadians were evenly split on their foreign minister. Pearson was either a hero for salvaging peace from war or a traitor to the Mother Country.

That stark divide erupted in the House of Commons where the staunchly pro-British Conservative opposition mauled Pearson. One MP declared that he had “weakly followed the unrealistic policies of the United Nations” and had “placed Canada in the humiliating position of accepting dictation from President Nasser”. Future foreign minister Howard Green charged: “It is time Canada had a government which will not knife Canada’s best friends in the back.” He railed that Canada did not have the backbone to support Britain because “they were so busy currying favour with the United States.”

A Calgary Herald editorial summed up Pearson’s actions as “a face saver for the Soviet puppet dictator in Egypt…a rank disservice in the cause of peace.”

Clearly aware of the division in the county, some ministers in Louis St. Laurent’s cabinet were deeply concerned by the potential fallout. In one meeting, a senior minister expressed anxiety about effect on the Atlantic provinces. Another said the government would lose 40 seats in Ontario at next election. Made of very stern stuff, the formidable St. Laurent is said to have replied: “You’re just talking with your blood.” And he was right. Foreign wars have all too often cut to the core of local politics.

|

|

MYTH 8:

Suez was a Turning Point for Canadian Foreign Policy

For Pearson and his colleagues, Suez was convulsive, Suez was challenging. At times it was even excruciating. But at its core, the crisis was nothing new. As the cliché goes, Canada was born from the clash of empires. Almost by default, the former colony and later middle power had to evolve and unfold within the orbits of different empires. Thus virtually every Prime Minister has had to contend with imperial summons to foreign fields. Each one of the summons has divided the country in some fashion. While we acquiesced to join the Great War, the Second World War, Korea, the Gulf War and Afghanistan, we have also maintained a strong tradition of staying put.

Macdonald refused to send Canadian troops to join a British military mission in the Sudan. Laurier struggled to stay out of the Boer War. King turned down London when they wanted Canadian forces at Chanak. Pearson declined to send Canadian troops to Vietnam. Chretien kept Canada out of Iraq. Suez fits very neatly into this stream.

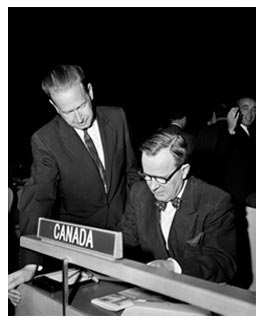

Challenging these myths in no way detracts from Pearson’s stunning achievement. Anyone who saw him close-up during those desperate hours has only praise and wonder. His right-hand man in the crisis, John Holmes wrote privately afterwards, “The boss was in the most extraordinary form I have ever seen. His mind was so clear that I found myself quite lost. Everything he said in public or private seemed to strike exactly the right note...[he] was operating beyond our comprehension and really had no need of advice.”. In his memoirs, then British Chancellor of the Exchequer Harold MacMillan was grateful for Pearson’s intervention: “Both by his personal powers of negotiation and by the respect in which he was held, he was able to exercise throughout the crisis a modifying and humanizing influence.”

Who needs any myths about Pearson’s diplomacy when the truth of what happened is still 50 years later so utterly remarkable.

Antony Anderson

Toronto

December 2007

|

|

|